Employment and Labor Law Risks

Overview

Farmers markets need to be aware of how employment laws affect their business or organization. Many markets do not sufficiently understand the complexity of employment law. Confusing though it may be, not knowing the law is not an excuse for violating it. Further, employment law focuses on the facts of a situation, not on titles. For example, a farmers market might use “intern” as a job title and operate on the assumption that that person is not an employee. Yet, under the law, an intern might be an employee and employment laws apply, regardless of the job title.

The bottom line is that every farmers market must research and understand employment laws in detail. These rules are detailed, and enforcement by workers, state regulators, and federal regulators is not uncommon.

Farmers markets have very few, if any, ways to minimize liability once an employment or labor law violation occurs. It is best to prevent a violation in the first place. This section explores a few steps to promote compliance.

For an overview of employment and labor law as a legal risk, see page 6 of this printable resource.

How to Manage this Risk

Employment Classification Risks

To understand and manage their legal risks, farmers markets should understand employment classification and properly classify their workers as employees, independent contractors, volunteers, or interns. Properly classifying market workers has many benefits, including:

- reducing the risk of non-compliance with employment and labor laws;

- managing the risk of liability for personal injury and property damage;

- creating suitable opportunities for employment, business, and community involvement; and

- promoting a fair and equitable work environment.

Properly classifying workers as volunteers, interns or apprentices, independent contractors, and employees can be very complex. The sections below introduce the basics and offer a few resources with more information. For comprehensive information, farmers markets will want to speak with an employment law attorney licensed to practice in their state.

Classifying Farmers Market Managers as Independent

Legally speaking, an independent contractor is a small business owner who provides their own tools and resources, is paid a flat fee, and is in control of when and how the work is accomplished. The more control the farmers market has over when and how a worker does their job, the more likely the person would legally qualify as an employee, not as an independent contractor.

Businesses and nonprofits that hire independent contractors do not need to cover payroll taxes, workers’ compensation insurance, or unemployment insurance for the independent contractors. As such, many businesses and nonprofits are motivated to hire independent contractors. What many don’t realize is that there are strict rules defining who is and is not an independent contractor.

What role do market managers play?

Farmers market managers – also known as market operators, market coordinators, market assistants, and other similar titles – are often the main point of contact for a farmers market team on market day. Although specific duties may differ between markets, market managers generally oversee market day operations, marketing efforts, vendor relations, customer relations, and food access programs and often serve as the contact for administrative matters.

Markets should have a written job description for their market manager. (This is a part of good recordkeeping!) Many sample market manager job descriptions can be found online, such as on the Farmers Market Coalition Resource Library, but markets should keep in mind that every market is unique, and what works for one market may not work for another, particularly when the markets don’t share similar governance structures. Markets may want to check with their state farmers market association as they create a job description for their market manager.

Why is employment classification for market managers important?

The legal relationship between a farmers market and its market manager is determined by the facts and circumstances of the relationship and not the market manager’s title. Understanding how to properly classify a market manager can help a farmers market manage the risks of employee misclassification. The risks of violating employment and labor laws include fines and costs associated with going to court. Proper employment classification can also ensure a fair working environment where the work of market managers is justly compensated and protected.

What are potential employment classifications for market managers?

What are the risks of employee misclassification?

There are several risks associated with the misclassification of an employee as an independent contractor (or volunteer):

- A federal or state agency may order payment of penalties.

- A federal or state agency may order payment of back taxes, including payroll and unemployment taxes, with interest.

- A misclassified employee may sue for unpaid wages and benefits. Liability for these costs can fall on the farmers market itself, as well as on any individual director or officer who played a role in the misclassification or failure to pay wages and benefits.

- Insurance, including commercial general liability (CGL), directors and officers liability (D&O), and even employment practices liability (EPL), generally does not cover penalties, back taxes, or unpaid wages and benefits.

The costs for paying penalties, employee-related taxes, and potential litigation can add up and be a serious threat to the success of a farmers market. The best way to manage this risk is by understanding employment classification and properly classifying market managers and other farmers market workers.

What determines a market manager’s employment classification?

Proper classification of workers is purely fact-based—each situation is unique and requires an understanding of the facts surrounding a particular worker’s duties and responsibilities. Titles do not determine the classification of a worker. Regardless of the relationship a farmers market and a market manager may believe they have, the market manager’s classification is based on the facts of how the manager completes their duties and responsibilities.

To manage the risks associated with employee misclassification, farmers markets should understand how different classifications are determined. An employer-employee relationship is assumed under the law, unless one can prove the worker is an independent contractor.

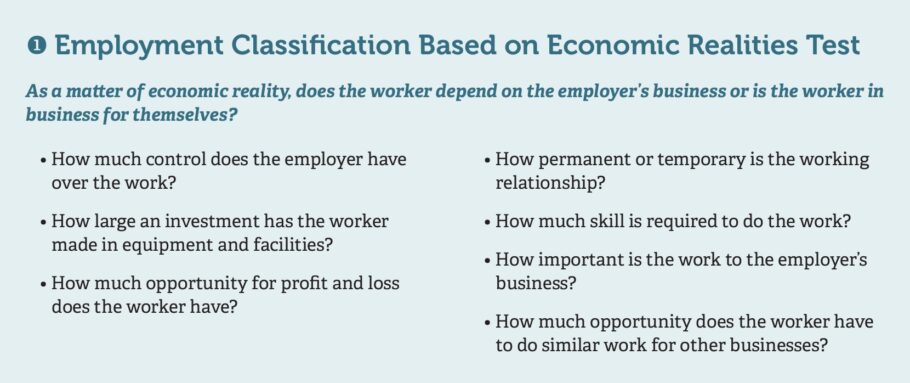

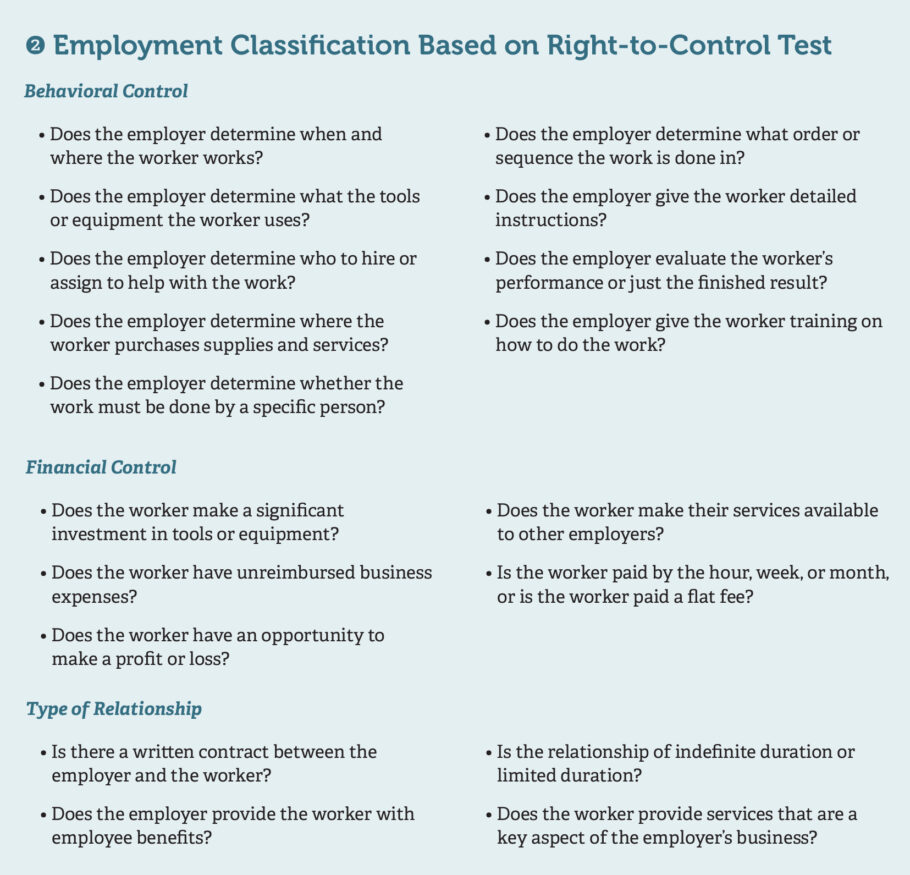

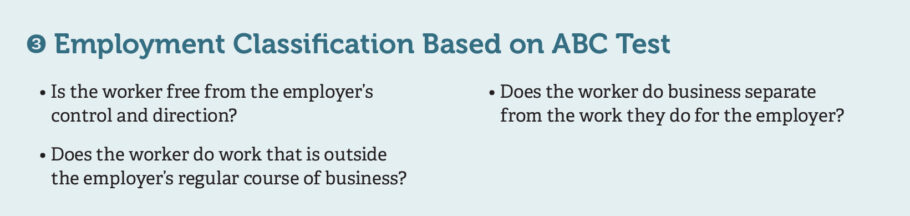

There are different tests that exist to determine whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor, including the economic realities test, the right-to-control test, and the state-adopted ABC test.

- The economic realities test helps determine a worker's classification for federal employment law purposes.

- The 20-factor or right-to-control test helps determine a worker's classification for federal tax purposes.

- Many states use a version of the ABC test to help determine a worker's classification for purposes of state employment, workers compensation, and unemployment insurance laws.

These tests are truly guides that require a balancing of the factors considered to determine whether a worker is an employee or independent contractor. In any given situation, certain factors may weigh more heavily than others. Markets that want to classify their market manager as an independent contractor should ensure the market manager meets the criteria under all of the tests, so the market complies with federal and state employment and tax laws.

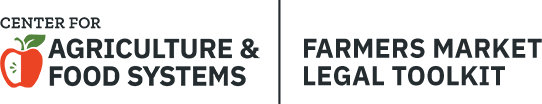

Courts have created the economic realities test to analyze whether a worker is an employee or independent contractor under federal employment law. The economic realities test weighs a set of factors to determine the worker’s economic dependence on the employer. Specifically, the economic realities test weighs these five factors: degree of control over the work; investment in equipment and facilities; worker’s economic opportunities for profit and loss; permanency of the work relationship; and skills required to complete the work. The U.S. Department of Labor balances the factors of the economic realities test as well as others to determine whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor. Some of these additional factors include how integral the services of the worker are to the business and the ability of the worker to have a business outside of the services they are hired to provide.

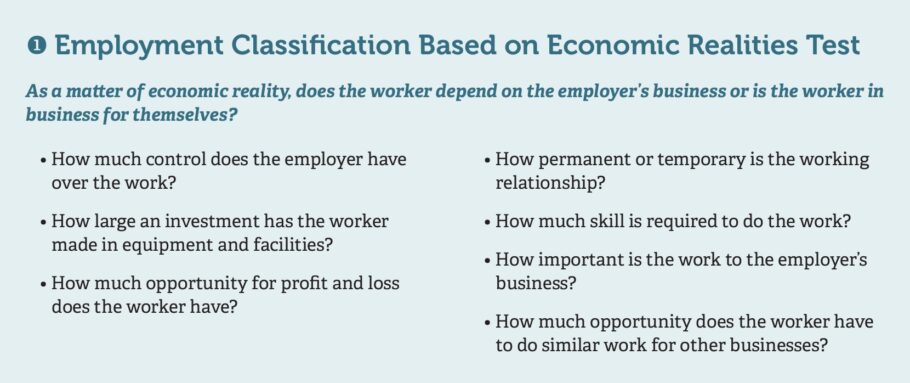

The IRS provides a right-to-control test (formerly known as the 20-factor test) to determine whether a worker is an employee or independent contractor for federal tax purposes. Generally, the test is divided into three categories: behavioral factors, financial factors, and the type of relationship that exists between the employer and the worker. The test is a guide for examining the entire relationship between the employer and the worker. Essentially, the focus of the right-to-control test is on the degree of control over the worker’s responsibilities and the worker’s abilities to engage in other work.

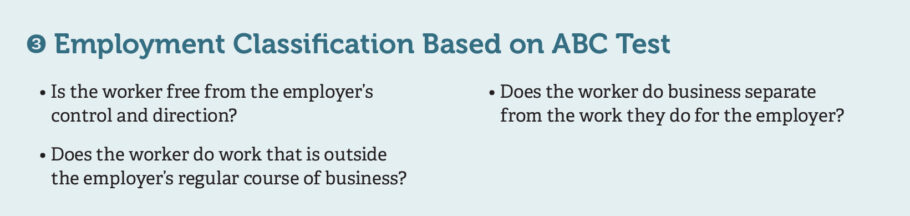

Most states have adopted a version of the ABC test to determine whether a worker is an employee or independent contractor for purposes of the state’s employment, workers compensation, and unemployment insurance laws. Some states may differ on the language for some of these factors, but the ABC test generally considers three factors:

- How much control and direction the employer has over the worker

- Whether the worker does the regular business of the employer

- Whether the worker does business separate from the work they do for the employer

The ABC test is quite specific and often, under this test, workers are considered employees and not independent contractors. It is important that farmers markets refer to state employment and labor laws to determine the most appropriate factors to consider in classification.

How does this apply to farmers markets and market managers?

Consider the following hypothetical example:

- Farmers Market A hired Manager B to manage its weekly farmers market.

- Farmers Market A’s board spent two weeks training Manager B to manage the market according to its 30-page manual.

- Among other duties, the board trained Manager B to draft an email with 10 specific categories of information to market vendors and customers, get approval from the board for the draft, and then send the approved email to market vendors and customers three days before market day each week.

- The board also trained Manager B to draft a report with 10 specific categories of information to review with the board three days after market day each week.

- Manager B spent close to 40 hours a week working on the email, report, and the other duties the board assigned them.

Under the economic realities test, the IRS 20-factor right-to-control test, and the ABC test, Manager B likely is an employee. Farmers Market A exercises the level of control that characterizes an employment relationship. Even if Farmers Market A and Manager B believe and want them to be an independent contractor, based on the fact that Farmers Market A has significant control over the way they perform their duties, they are likely an employee.

Classifying a new market manager

Proper classification is a good risk management practice and should be considered before hiring a market manager. This is an opportunity for a farmers market to decide how much control it wants over how the market is managed. Being clear about a market manager’s classification before hiring can lead to better working relationships within the market and allow the market to focus on the goals it has for the market and community.

Reclassifying an existing market manager

If a farmers market realizes that a market manager whom it treated as an independent contractor is actually an employee, the farmers market must comply with employment and labor laws. Any taxes due should be paid, and employment and labor laws should be complied with. The IRS offers a program called the Voluntary Classification Settlement Program, a limited amnesty program to help entities that willingly wish to properly classify their workers reduce their liability for payroll taxes, interest, and penalties.

If a farmers market wants to change their market manager from an employee to an independent contractor, the market should proceed cautiously to reduce the level of control it exercises over the market manager and make any other changes necessary to ensure there is no employment relationship under any of the tests. Additionally, the farmers market cannot fire the market manager from being an employee just so that they may later become an independent contractor.

Key takeaways

- Proper employment classification of market managers is important to avoid the risks of employment and labor law violations.

- Proper employment classification is purely fact-based. The facts surrounding the work and how the work is done are legally relevant, rather than what the parties call their relationship. Titles do not matter; facts do!

- The economic realities test is the legal test that determines whether a worker is an employee or independent contractor for federal employment law purposes.

- The right-to-control test is the legal test that helps determine whether a worker is an employee or independent contractor for federal tax purposes.

- Farmers markets should look to their state employment and labor laws to understand what test their state uses to determine whether a worker is an employee or independent contractor.

Classifying Farmers Market Staff as Volunteers

Legally speaking, for-profit businesses (sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability companies, corporations, and cooperatives) cannot have “volunteers.” Under the law, a volunteer is a person who gives his or her time to government or charitable purposes. For this reason, if a person is “volunteering” for a for-profit business, they do not meet the legal definition of a volunteer. Rather, the law will see anyone who does the work of a for-profit business an employee. Under the law, to “employ” someone is to allow a person to do work for a business, so even those who agree not to accept money for their labor are still employees. Technically, the worker could be an employee or an independent contractor, depending on the circumstances (see the section on independent contractors below).

There are legal limits on the ways nonprofits can use volunteers as well. Volunteers should not be an essential feature of a nonprofit’s workforce and should not be dependent on the organization for a living.

The Role of Volunteers at Farmers Markets

Volunteers are critical to the success of many farmers markets. They can connect markets with their local communities. They can maximize limited market resources. They can also perform work that is impractical or inefficient for employees to perform. The USDA’s 2019 National Farmers Market Managers Survey demonstrated the significant role volunteers play in farmers markets — 62.4% of farmers markets have at least one volunteer working at the market, and 31,609 people volunteered at farmers markets in 2019.

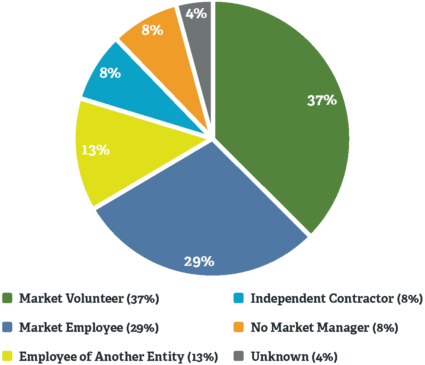

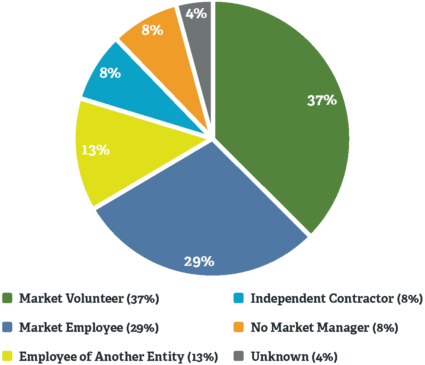

Farmers Market Managers in 2019

The survey results showed that farmers markets most commonly considered their market manager a volunteer. Nationally, 37% of markets relied on a volunteer market manager. Markets in rural communities (50%) and suburban communities (49%) used a volunteer manager more than markets in urban communities (32%). Other markets, particularly those in the western United States (48%), paid an employee or independent contractor to manage their market, and a minority of markets (13%) relied on another entity’s paid employee to manage their market.

Most markets operate under a board of directors or similar decision-making group. Members of market boards, steering committees, or other decision-making groups are also often volunteers.

Who Counts as a Volunteer under Federal Law?

To determine the proper classification for a worker, a farmers market must understand how the law defines a bona fide volunteer and the particular facts and circumstances surrounding the market, the worker, and their relationship. A worker’s title does not determine proper classification, and an agreement or understanding between the market and the worker does not determine proper classification.

A volunteer is an individual who provides services to a public agency or a religious, charitable, civic, humanitarian, or similar non-profit organization as a public service and without the promise, expectation, or receipt of compensation for their services.

The primary and relevant federal law for determining whether a worker is an employee or a volunteer is the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). This federal law established minimum wage, overtime, and other standards for employees. Under the FLSA, individuals may volunteer for government agencies. Individuals may also “volunteer time to religious, charitable, civic, humanitarian, or similar non-profit organizations as a public service and not be covered by the FLSA” standards that apply to employees. The FLSA does not distinguish between nonprofit organizations that have or have not been recognized as tax-exempt by the IRS in its treatment of volunteers, but federal law clearly prohibits individuals from volunteering services to for-profit businesses, which include sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability companies, for-profit corporations, and cooperatives.

Under the FLSA, a volunteer is narrowly defined as “an individual who performs hours of service . . . for civic, charitable, or humanitarian reasons, without promise, expectation or receipt of compensation for services rendered.” On the other hand, an employee is broadly defined as an “individual employed by an employer,” and “employ” is broadly defined as “to suffer or permit to work.”

Volunteer: “An individual who performs hours of service . . . for civic, charitable, or humanitarian reasons, without promise, expectation or receipt of compensation for services rendered.”

Employee: An individual “employed by an employer,” where “employ” is defined as “to suffer or permit to work.”

These definitions were designed to prevent employers from avoiding FLSA requirements by pressuring workers to volunteer their services. To further guard against coercion, a worker employed by a nonprofit organization or government entity cannot perform work that is similar to their regular work duties as an unpaid volunteer for the same entity. To guard against unfair competition, a worker cannot volunteer for the commercial activities of a nonprofit organization or government entity, such as operating a gift shop.

To determine whether a worker is a bona fide volunteer, the U.S. Dept. of Labor considers several factors:

- Is the employer a nonprofit organization or a government entity?

- Does the worker offer their services freely without pressure or coercion?

- Does the worker expect to receive or receive any compensation for their services?

- Does the worker perform services on a part-time basis?

- Does the worker displace any of the employer’s regular employees?

- Does the worker perform services that are typically associated with volunteer work?

What Counts as Compensation under Federal Law?

Volunteers cannot receive compensation for their services. Compensation includes money in addition to anything of value (such as free produce or waiver of vendor fees). On the other hand, federal law allows volunteers to receive “expenses, reasonable benefits, a nominal fee, or any combination thereof, for their service without losing their status as volunteers.” Whether the amounts associated with these expenses, fees, or nominal benefits would compromise a volunteer’s status as a bona fide volunteer under the FLSA is determined by looking at the total amount of payments made “in the context of the economic realities of the particular situation.” A court considering this issue would use a test called the ”economic reality test,“ which weighs a set of factors to determine the worker’s economic dependence on the employer.

Generally, volunteers are allowed to receive reimbursement for costs related to their volunteering (such as mileage reimbursement for travel). A nominal fee cannot be a substitute for compensation and cannot be tied to productivity (such as hours of work). In some situations, the U.S. Department of Labor has found that a fee is nominal if it is not more than 20% of what an employer would otherwise pay an employee for the same services. It is also important to know that volunteers are not protected under the Volunteer Protection Act (discussed in more detail below) if they receive benefits valued at more than $500 a year.

What About State Laws?

If federal and state laws differ in how they define “volunteer,” farmers markets must follow whichever law provides greater employment protections to workers. Therefore, markets need to understand both federal and state employment laws. State departments of labor are a good resource to find out about a state’s laws.

State laws vary in how they define the employment relationship and/or volunteer. However, many states’ employment standards laws were modeled after the FLSA and are interpreted similarly to the FLSA. In addition to employment standards laws, state unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation laws sometimes define the employment relationship for purposes of those laws.

Hypothetical Examples

Manager is likely a volunteer.

- Farmers Market is a nonprofit charitable organization that operates a small weekly farmers market.

- Vendor, a farmer who sold at Farmers Market’s market and voluntarily worked about five hours/week managing the market without compensation, retires.

- Daughter, Vendor’s adult daughter, offers to take over for Vendor because Daughter wants the community to continue having access to fresh, local food.

- Daughter spends about 20 hours/week for eight weeks preparing for the new market season and recruits 10 new market vendors.

- As a gesture of appreciation, Farmers Market gives Daughter a gift certificate to purchase $250 in produce from market vendors throughout the season.

Daughter is likely a bona fide volunteer. Farmers Market was a nonprofit charitable organization. Daughter offered their services freely without pressure or coercion. Daughter did not expect or receive compensation beyond a nominal fee of $250. Daughter worked part-time. Daughter performed services that were previously performed by another volunteer.

Manager is likely an employee.

- Farmers Market is a nonprofit charitable organization that operated a small weekly farmers market.

- Farmers Market’s long-time employee, who worked 15 hours/week at $15/hour to manage the market, retired.

- Vendor, a farmer who sold at Farmers Market’s market, offered to manage the market for its 20-week season. All Vendor asked in return was for Farmers Market to waive the $100/week vendor fee.

- Farmers Market readily agreed, as it would not have to hire and pay for a new part-time employee.

Vendor is likely an employee. Although Farmers Market was a nonprofit charitable organization, and Vendor offered their services freely without pressure or coercion and worked part time, Vendor expected to and did receive $100/week in compensation for their services and eliminated a part-time employment position.

Legal Risks and Risk Management

Some of the legal risks of misclassifying employees as volunteers include:

- A federal or state agency could order a market to pay back taxes, including payroll and unemployment taxes, with interest.

- A federal or state agency could order a market to pay penalties for failure to pay wages, pay unemployment taxes, or purchase workers’ compensation insurance.

- A federal or state agency could prohibit a market from accessing government contracts for a specified period of time.

- A misclassified employee could sue a market for unpaid wages and benefits. Liability for these costs could fall on the market itself, as well as any individual director or officer who played a role in the misclassification or failure to pay wages and benefits.

- Insurance, including commercial general liability (CGL), directors and officers liability (D&O), and even employment practices liability (EPL), generally does not cover a market’s misclassification-related penalties, back taxes, or unpaid wages and benefits.

Employment-related taxes, interest, and penalties; back wages; attorney fees; and court costs can add up and pose a serious threat to the success of a farmers market. The best way to manage this risk is by understanding employment classification and properly classifying farmers market workers.

Some of the legal risks of using volunteers include:

- A market could be liable (i.e., can be sued) for damages if a volunteer who is not covered by the market’s workers’ compensation, CGL, or other insurance gets ill or injured or their property is damaged.

- A market could be liable for damages if a volunteer whose actions are not covered by the market’s CGL or other insurance negligently causes a vendor or customer injury or property damage.

Some of the legal risks of being a volunteer include:

Farmers markets and their leaders should be aware of the risks they bear, but they, in addition to the volunteers themselves, should be aware of the legal risks volunteers assume when they volunteer, whether as board members, market managers, or day-of-market workers.

The federal Volunteer Protection Act (VPA) defines a volunteer as an individual performing services for a nonprofit organization or government entity as a director, officer, trustee, or direct-service volunteer who does not receive any compensation other than reasonable expenses or any “thing of value in lieu of compensation in excess of $500 per year.”

Under federal law, a nonprofit organization or government entity’s volunteers are not liable for harm they cause third parties (like vendors and customers) while they are acting within the scope of their responsibilities for the entity, but there are limitations:

- If volunteers don’t have a required license, certification, or authorization for what they are doing, they are not protected against liability.

- If volunteers cause harm “by willful or criminal misconduct, gross negligence, reckless misconduct, or a conscious, flagrant indifference to the [victim’s] rights or safety,” they are not protected.

- If volunteers cause harm when they are operating a motor vehicle, vessel, aircraft, or other vehicle that requires an operator’s license or insurance, they are not protected.

The VPA does not protect nonprofit organizations or government entities—only volunteers themselves, and it does not protect volunteers from liability to the nonprofit organizations or government entities they work for—only to third parties.

How farmers markets can manage their legal risks:

- Understand employment classification, and properly classify your market’s workers.

- Avoid using volunteers if your market is a sole proprietorship, partnership, limited liability company, for-profit corporation, or cooperative.

- Limit the amount and type of services volunteers provide your market.

- Require volunteers to sign a waiver that releases your market from liability.

- Obtain appropriate insurance to protect your market, its leaders, and its volunteers.

- Implement volunteer application and screening procedures.

- Conduct volunteer orientation and training and create a volunteer handbook.

- Maintain records for each volunteer and their hours worked.

Classifying Farmers Market Staff as Interns and

Legally, when farmers markets hire “interns” or “apprentices,” they are offering an educational experience in exchange for lower wages or benefits. Most markets treat interns differently from other employees in terms of payroll and employment procedures. Legally speaking, at for-profit businesses, all interns and apprentices are employees and meet the same legal requirements as any other employee. This means a market would likely need to pay interns at least the minimum wage and workers’ compensation, among other requirements of employment law.

An exception occurs if the internship meets the six criteria laid out by the federal Department of Labor (detailed in Fact Sheet 71), which include that the business may not benefit from the labor of the intern and that if the intern were not present, no one would need to be hired instead. At least one court decision has taken a broader view of when workers can be considered interns. It considered several factors like those in the Department of Labor fact sheet, but its analysis emphasized whether the focus of the internship was on education and whether the intern, not the employer, was the primary beneficiary of the work relationship. This area of law is somewhat in flux—for questions specific to your market, consult an attorney licensed in your state.

Interns at nonprofit operations are different. In that case, the individual may legally be considered a volunteer, as discussed above.

Employment Law Obligations

Many farmers markets discover at some point that their volunteers, interns, and independent contractors are actually employees under the law. What does this mean? This means the market is obligated to follow all employment laws. The section below discusses the requirements of three aspects of employment law.

Minimum wage

Generally speaking, every employee must be paid at least the minimum hourly wage under state law. In some states, farm operations are an exception to this rule. This exception does not extend to farmers markets. Farmers markets are regular businesses that must follow minimum wage rules. Nonprofits are also held to minimum wage requirements and nonprofit employers must pay their employees at least the minimum wage, just like for-profit businesses.

Workers’ compensation

Workers’ compensation is a program that provides coverage for individuals injured in the course of employment. It works much like an insurance policy. The employer pays the premiums and injured workers are eligible to make claims for coverage. Workers’ compensation programs are established by state law, and the procedures for purchasing and using workers’ compensation are set by statutes and regulations.

The original purpose of workers’ compensation was to protect employers just as much as employees. Prior to the creation of workers’ compensation programs, employees who were injured could sue their employers for the unsafe working conditions that caused their injuries. Employers had to spend a lot of money to defend themselves in lawsuits or deal with unpredictable outcomes and jury awards. Workers’ compensation solves this problem faced by employers. Now, where workers’ compensation is available, an injured employee is prohibited from suing his or her employee regardless of the circumstances that caused the injury. In exchange, businesses must provide safe working conditions. These conditions are regulated through the Occupational Safety and Health Act rather than through individual lawsuits, by and large.

Nearly every business and nonprofit is required to carry workers’ compensation coverage. Some states have limited exceptions for small businesses or nonprofit businesses. Workers’ compensation is different in each state, and each farmers market will need to investigate obligations in their own state. State departments of labor and private insurance agents are good sources of more information.

Unemployment insurance

Unemployment insurance is a tax collected by the government from employers through the payroll process. The business is responsible for paying this tax, not the employee. The money collected goes into a fund to compensate workers who have lost their jobs through no fault of their own. Both the federal government and the states run unemployment insurance programs. The amount of tax paid by a business depends on several factors. The current resources of the total fund and the level of unemployment at the time are major factors. An individual employer’s history also affects the business’s tax rate. Businesses whose former employees utilize the unemployment insurance program pay a higher tax rate. Generally, all businesses including nonprofits must pay unemployment insurance tax. Small farms are not required to pay for unemployment insurance, but this exception does not extend to farmers markets.

The Small Business Administration (SBA) helps businesses understand how to comply with employment laws, and they have offices throughout every state. (Find one near you at www.sba.gov.) Of course, state departments of labor and employment are also good resources.

Resources for Worker Classification

Download a PDF of the full resource for how and why to properly classify farmers market managers as employees or independent contractors, Employment Classification for Farmers Market Managers.

For detailed information on working with volunteers at farmers markets, download a PDF of the full resource, Volunteers at Farmers Markets: Managing Legal Risks.

For extensive details on classifying workers as volunteers, interns, and independent contractors as opposed to employees, see Farm Commons’ resource Classifying Your Workers: Employees, Interns, Volunteers, or Independent Contractors?

For more details on the specific risks of using interns and volunteers at for-profit and nonprofit businesses, see Farm Commons’ guide Managing Risks of Interns and Volunteers.